My patrilineal grandmother was a Gordie, born in 1903 in Gateshead on Tyne near Newcastle in the UK. She came to Australia on a sailing boat. A woman whom my tough central London mother and my Aunty by marriage, both recall as being judgemental and unsupportive. They knew her as a strict Presbyterian, who in their experience made little accommodation for them during vulnerable times in their lives, when they had new babies and wayward husbands. My mother recounts a tally being totted up, to cover the cost of the food we ate when dad bunked off to Melbourne for a while. As an almost direct consequence of my mother not feeling welcome – we left Australia on an ocean liner before I turned one. My grandmother was the mother of three boys, an amateur painter and lived to be one hundred and five. She remains one of my few heroes.

One of the few photos I have of the early years of my life, is a photo of my mum, my dad, my brother, and me on an ocean liner leaving Australia and heading to the other side of the world. A thin white border contains the exuberant scene that captures us in black and white, pressed amongst an excited throng of fellow travellers. Recently thrown streamers hang over the balustrade. I am in the arms of my mother and wearing an almost outrageous party dress of tulle and frills. My white-blonde, wispy curls soften my serious countenance set amongst a sea of exuberant smiling faces. Looking back the scene becomes a movie still in my mind – a gleaming detail which holds within it the complexity of the act of leaving – undoubtedly laced with both joy and melancholy and other less easy to define emotions. My party dress and the streamers each a symbol of hope for a bright future and a mask for the ache of sadness for what might have been. A refrain that I suspect plays at various times in the musical scores of the lives of those who have ever made choices that closed one door and opened another.

A woman of my grandmother’s generation, artist Clarice Beckett (1887 to 1935) made a life shaping decision when she chose the life of an artist over marriage and children. Although eventually she became the carer to her aging mother and father, so she didn’t completely avoid the nurturing responsibilities often left to the women of her era. Perhaps unavoidably my recent experience of the exhibition Clarice Beckett – Atmosphere, at Geelong Gallery, was loaded with grandmotherly frames of reference, not least because Clarice would have been a young woman when my grandmother arrived in Australia. Compounded by the fact that I have recently assumed the signifier of grandmother as our first born had her first born as close to the top of the world as we live to the bottom.

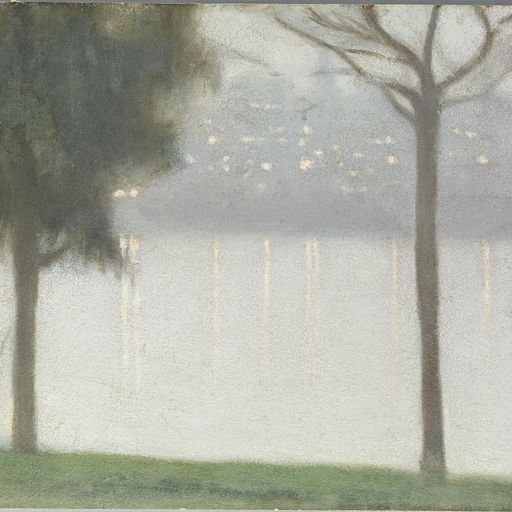

During a recent trip to regional Victoria where I had the pleasure of meeting the new grandchild’s other grandmother, who is a painter and an altogether lovely person, I also had the pleasure of seeing Clarice Beckett – Atmosphere, at Geelong Gallery. In this thematically curated survey show, each painting operates like a portal, presenting us with a window into Clarice’s world as she sees it, in a particular moment in time. She offers us, cropped views of Melbourne streets and country laneways, and vistas of coastal Victoria. Her small-scale works speak of time spent in and with her chosen location around the region/s she called home. Clarice turns these scenes into what can be described, although inadequately, as landscape paintings, such as Across the Yarra, c. 1931, or Evening light, Beaumaris c. 1925. Just as a biography reveals not only the nuanced complexity of individual characters and relationships, but also begins to reveal their legacy, a survey show of a single artist allows us to feel our way towards a deeper relationship with their body of work and its place within the larger narratives of art history and art criticism.

It is easy to be seduced by Clarice’s work, to enjoy the representational qualities of scenes rendered with a thoughtful, responsive touch, which speak of an openness to visual experience, a painterly rigour, and an intellectual curiosity. As I imagine the process of making these paintings I think about Clarice as a single woman, carving out time to move through the landscape, set up her art supplies from her self-designed cart, painting outdoors, in the fresh air, or working en plein air as the French Impressionist would say. I wonder, was the weather kind, did the heat and wind effect the way the paint behaved, did flies and insects make their presence felt and did passers-by stop, and talk to Clarice whilst she was trying to concentrate.

People do occur in her works, although they appear more for scale, texture, and painterly contrast than as representations of individuals. Everything in these works is first and foremost, a painterly gesture, they are abstractions, anchored-in or leaping-from lived experience. The way Clarice handles paint, and the abstract qualities of her street scenes and mostly coastal and river landscapes, lead critics to describe her as a part of the international Modernist shift away from representation and towards abstraction. There is a seriousness to her endeavour, she is not satisfied with likeness, she is aiming for something essential in the scenes she paints, something that can be described as the elemental life force or in more clearly spiritual terms as the divine.

One of Clarice’s early paintings, Still life with fish, plate and bottle c. 1919, which I’ve only seen in reproduction, reminds me of Jean Baptiste Chardin’s Still life with plums, c 1730. I will forever see the small Chardin painting, which is in the collection of The Frick Museum, in New York as a portal to the divine. I encountered the work under natural light, when The Frick’s Head of Education, Rika Burnham, arranged to have the gallery lights turned off, and the work taken down from the Gallery wall and placed near a window. This allowed the small audience, who gathered around the object with all the intensity of devotees encountering a religious relic, to see the work in similar conditions to which it would have been made. As the evening drew in and the light altered, the work moved deeper into our collective consciousness and opened me, to a more metaphysical relationship with the subject. I carried the resonance of my encounter with Chardin’s Still Life with Plums, into my experience of Clarice’s exhibition. I recognised something of the same kind of reverence that Chardin showed for his modest still life subject in Clarice’s approach to her subjects. This openness to the mystery inherent within prosaic subjects and vistas was well supported by the curatorial decision to present Clarice’s work under subtle lighting. The restrained lighting allows the works to speak softly for themselves as viewers, lean into the experience, without the bright spotlights common in contemporary galleries.

Clarice’s paintings are carefully selected envelopes of landscape, not compressed but intensified through careful observation. There’s consistently a feeling of the personal in her work, a feeling of intimacy that carries through the exhibition, even though we’re looking at seascapes or cliffs, suburban roads, or urban streets, which are by their nature – public. There is always a sense of some ‘one’ who is doing the looking and some ‘place’ where the looking is occurring. From this situated encounter Clarice, a subtle colourist, creates tonal colour modulations that sweep over us as though she is throwing a soft mantle over the landscape and drawing us into it.

Nocturne, 1931 is a work where the abstract qualities start to take over from the representational aspects as the cloak of night time reduces the details in the bayside scene. The work is described in accompanying material as about mood, such as loneliness, longing or melancholy which are complicated emotions that suggest lack. I want to describe the quality that the painting is capturing as aloneness, encouraged in part because I kept wondering: Was Clarice sitting alone at night painting this scene? Which raises ideas about gender and safety which are not the subject of my essay but exist in my mind like a form of hauntology. Aloneness in the landscape, safety issue aside, could also suggest someone in touch with nature, in a meditative, peaceful state. Anyone who has cared long-term for the needs of others might even delight in time alone. The softening of the demarcation between forms in Nocturne, sees the painting becomes more spatially expansive – like a cosmos. Nocturne is a musical term and I read the dissolution of forms and move towards abstraction in Clarice’s Nocturne as an invitation to a different kind of relationship for the viewer, one that is more akin to music in its collaborative nature, informed by the mood temperament and history of the audience.

In, The first sound, c.1924, we see a horse and cart coming over the hill, in a soft-edged, misty morning light and can easily imagine the clip clop of the hooves breaking the morning silence. Clarice’s quiet, evocative painting convinces me that I have heard that sound although I have no such memory that I can call to mind. This fugitive memory is perhaps evidence of the influential Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious that suggests some memories are common across humanity and originate in the inherited structure of the brain, as opposed to our personal unconscious which is built from our individual lived experiences. A concept which disrupts the idea of absolute individuality, replacing it instead with a very reassuring concept of human commonality where it seems quite possibel to arrive at the universal through the deeply and exquisitely personal.

In Clarice’s own words, she described her job as a painter as:

to give a sincere and truthful representation of a portion of the beauty of Nature and to show the charm of light and shade, which I try to give forth in correct tones so as to give as nearly as possible an exact illusion of beauty. Clarice Beckett, 1923 ‘Twenty Melbourne Painters’, exhibition catalogue.**

She reaches towards describing the scene she is painting, through an intimate engagement with the location, by which I mean an exchange that is personal and involves time spent in and with the landscape as its moods and tempers change. Clarice was a Modernist, finding her way towards a universal language that was not tied to National borders, the universal language of tone and colour and form – the language of abstraction. Sometimes our aims fall short of our ambitions, but it is in the reaching towards an ideal that decisions are made, and consequences ensue, painterly consequences, ideological consequences and pragmatic consequences. Clarice died at just 48 years old after catching pneumonia brought on while trying to catch the atmospheric effects of a coastal storm, although not all consequences are that cataclysmic. Clarice’s reputation faded after her early death, until her legacy had life breathed into it by Dr Rosalind Hollinrake, who after saving approximately 370 of 2000 of Beckett’s works from an open-sided shed in rural Victoria in 1970, has championed Beckett’s work for over five decades. I think it’s fair to describe both Clarice and Rosalind as women of conviction.

I re-met my grandmother when we returned to Australia, one week past my eleventh birthday. Whilst still Presbyterian she was no longer strict. It seems the decade in between us leaving and returning had softened her. Her faith had moved from being something that made her unwelcoming to the new mothers in her family, to being generous and accepting of her grandchildren. Her faith had become more spacious, a manifestation of love rather than an imposition of rigid expectations, responsive rather than coercive. The grandmother I knew saw God in every creative act, every sunrise, every bloom, every child’s face, every brush stroke that landed in the right place and every well-made bed.

My grandmother taught me how to paint a vase of flowers and how to make perfectly round pikelets, a technique I never mastered. For me, the space she made for me in her life, felt like what I would now describe, even though I am a heathen, as Grace. I use the term heathen not as a pejorative term but simply to indicate that while I talk of Grace and Divinity, I am not part of any formal religion. Lastly, I will share my ambition that I live my new role as a grandmother, with the kind of Grace and loving attentiveness that I experienced in my grandmother’s relationship to me. I also read Clarice Beckett’s relationship to her work with its desire and ambition, its attentiveness and care, and steadfastness of gaze, and weight within the canon of Australian art history as Grandmotherly, in the most complex sense of the word. A word that signifies not only position within a family, but also signifies, desire and vulnerability, public declarations of your position, loyalty and it seems to me the very real possibility for redemption or exile.

Clarice Beckett – Atmospheres, on exhibition at Geelong Regional Gallery, 1 April – 9 July 2023

* as quoted in, The present moment, The Art of Clarice Becket, Tracey Lock, Art Gallery of South Australia. p.172.