David Griggs is a thoughtful, softly spoken man whose words arrive with padded edges allowing us to bump into them with minimal harm. Just as he is committed in his art practice to a process of call and response where each gesture and passage of paint gives rise to the next – so too he makes room for the other when talking. His quiet integrity and respect for people saw his directorial film debut become a collaborative experience that David recounts as one of the most beautiful of his life. This disclosure from David, when he was the Artists in conversation with Maria Stoljar, from the popular podcast ‘Talking with painters’, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, in September 2022, was followed by a rolling, generous laugh – as he reflected that he wasn’t sure this collaborative approach was the best thing for the final film, but the process of collaboration …well … that was divine.

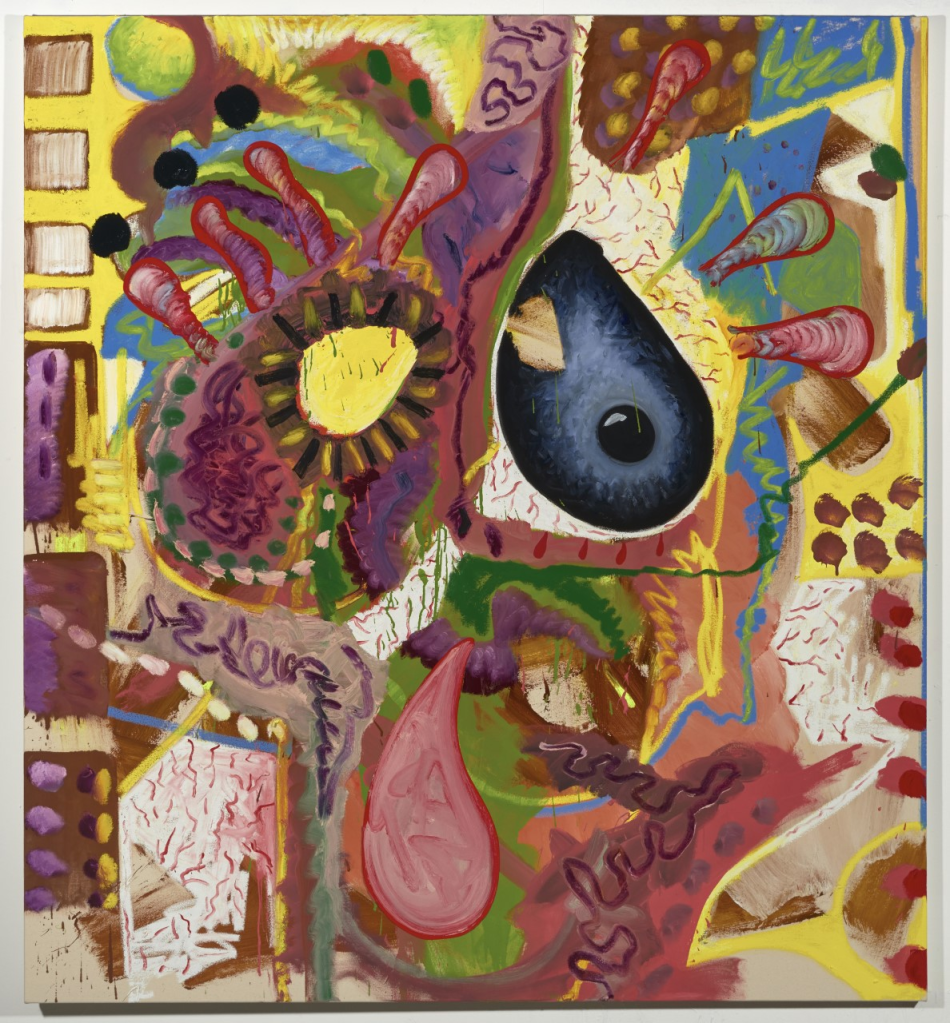

I read Griggs’s paintings as performative acts of visual autoethnography. I imagine as Griggs moves through the world, through international cityscapes and intimate suburban streetscape, that images silt up like sedimentary accretions creating an interior visual lexicon that David draws on in the process of making paintings. As his paintings, such as Untitled, 2022, pictured above, evolve, layer upon layer is added, often wet in wet, bringing a time-bound urgency to the process, which is revealed in the quality of immediacy in much of the mark making. Through the directness of his gestures and the way that colours, patterns, signs, and symbols energetically butt up against and layer over each other one feels one is bearing witness to an evolving, dynamic, journey-man’s record that suggests a narrative but eludes a definitive translation.

There’s a closeness to the surface, an openness to experience that I encountered through David’s work. Colours and shapes overlap and bounce off each other, eyeballs pop up. A cavalcade of characters appear across his body of work, routinely enough to be described as leitmotifs, such as skulls, cigarettes, eyeballs, with more abstract elements such as textured, surprising shapes, and purposeful, wobbly hand drawn curvilinear lines shaping and leading us around the world of the painting. In the push and pull between figuration and abstraction, the denseness of the imagery and the vibrancy of the colour choices overwhelmed me on first encounter. As I settle into a relationship with the work, the formal qualities reveal themselves to me, operating like a fluid, elastic framework from which hang traces of the cultural zeitgeist – coloured by David’s personal sensibility, such as in the artwork, The Second Lockdown, 2021, oil and resin on fabric on canvas, 150 x 450cm.

Jugendstil, 2019, acrylic, resin, oil on fabric on canvas, diptych, 199 x 367 cm overall, was exhibited in Mankini Island at Rosyln Oxley Gallery in February 2020. This intense work is painted on two fur, tiger motif blankets. As one can imagine the thick furry ground was frustratingly difficult to work with and yet he persisted – to create works that blend kitsch, representation, and abstraction, that ultimately hold the wall like an iconic and ironic history painting. Jugendstil, thumbs its nose at the tradition of the academy and the large format genre of history painting – a tradition that saw both iconic historic moments and mythic cultural narratives represented in glorious, large-scale detail, designed to uphold and at times prop up the status quo. History painting of the eighteenth and nineteenth century brought cultural legitimacy and influence for artists, as their work propagated nation building narratives through the lens of the dominant cultural group. David’s work holds cultural weight of a different anti-establishment, disruptive kind. Disrupting easy consumption David’s works offer an encounter with …. A way of being in the world. A collaborative, imminent way of encountering people, objects, places, and histories. These canvasses evoke a hectic, noisy, melange of collected deposits, traces, echoes, and impressions, accreted, and layered into the canvas like archaeological sub strata’s – that seem to be in process of constant realignment promising at any moment to erupt.

In David’s practice I see a bubbling up of cultural traces of the places David inhabits. David began a relationship with the city of Manilla in the Philippines as part of an artist’s residency. He recounts Manilla as a place where he found the kind of collaborative, energetic, generative, artistic exchange that he was trying to find in Australia. When he got to Manilla he found it – he didn’t generate it, it was already there, an artistic camaraderie between makers. Be they fine artist, poster painters or tattooists. In Manila David became part of an artistic community, not removed from the melee of life, but enmeshed with the thriving heartbeat of a big Asian city. I could be projecting all of this. I work in art galleries, which while open to all are a formal container for experience – framed by cultural convention and protocol. For me galleries are spaces of respite from the melee, they are full of life, but it is curated life whose formal and evocative qualities I delight in discovering and sharing with others. My professional life has been driven by a desire to connect audiences to contemporary art and in doing so make a space for myself – a reciprocal act of hospitality, with all the possible warmth, generosity, and risk that that implies.

For me, David’s works are compressed and complex, culturally framed narratives of intensity and emotion. In their most intense moments, I experience them as personal and cultural transcriptions of madness, addiction, and illness. When we encounter art together, we are ‘becoming-with’ (Harraway, 2016), collectively engaged in a process of bring the work into being, a process of ‘worlding’, (Harraway, 2016). Inherent in the move from the noun world to verb worlding is the proposition that the world is not static and complete but made anew in each encounter, between, people, places, species, and things. I am committed to the idea that artworks have agency and actively contribute, as do audiences and artists – to a potentially transformative, process of worlding – in which agency is not given but occurs in the unfolding of the exchange that in its co-created newness has the potential to be liberatory… or not.

After going to art school myself, to be an artist, then following a different path and spending two decades in art galleries working between artworks and audiences … I have come to understand that I don’t think like a painter. I think like a writer for whom words and language are my contribution to meaning, my pathway to connection. When I am encountering painting, I am to some extent cast adrift in a landscape where the lingua franca is foreign to me. If I want to receive what the painting is offering me, I must actively reach towards understanding. And in that reaching I inherently bring my localised, situated perspective, my history, my experiences, my prejudices. I am not always, but often, pressed up against the limit of my knowledge. Reaching with hand outstretched and one foot raised I am momentarily destabilised – inviting an encounter with otherness that I read as both risk and promise. I also consider it a reciprocal gesture of hospitality inviting otherness in and wanting otherness to make a space for me in a collaborative, performative autoethnographic act of being-with (Harraway, 2016).

Writer and auto ethnographer, Stacey Holman Jones (2011) when diffracting her writing and thinking on autoethnography through the thinking of philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler proposes the following:

Judith Butler writes, our willingness to risk ourselves—our stories, our identities, our commitments—“in relation to others constitutes our very chance of becoming human (Butler, 2005, p. 136 cited in Adams, Holman Jones, & Ellis, 2016, p.19).

For me, Griggs body of work is a time-bound, visual essay in becoming human, an essay that plumbs both personal and cultural depths. In the words of Holman, when advising readers what to do when in the receipt of auto ethnographic work,

let it be you who reads with feeling and solidarity. Let it be you who takes what experience tells and makes it into something you can use, something yours (Holman, 2011, p. 333, cited in Adams, Holman Jones, & Ellis, 2016, p.25)’.

A thoughtful provocation from a thoughtful writer that I am applying to a thoughtful painter’s body of work in the hope that it operates as an invitation to think your own thoughts, in your own way and that that way is useful to you.

Adams, Tony E. Holman Jones, Stacy & Ellis, Carolyn (2016). Handbook of Autoethnography. Routledge.

Haraway, D. (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Holman Jones, S. (2011) Lost and Found, Text and Performance Quarterly, 31:4, 322-341, DOI: 10.1080/10462937.2011.602709

All opinions expressed in this blog are my own.